SÃO PAULO – President Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva’s administration has sent important signals to Brazil’s landless rural workers regarding land reform, but those signals have yet to translate into concrete measures, the Bishops’ Conference’s Land Pastoral Commission (known in Portuguese as CPT) said in a brief review of 2025.

In an article on the progress and setbacks of land reform in Brazil last year, the CPT acknowledged that Lula has taken significant steps since the beginning of his third term in 2023. The most relevant was the reestablishment of the Ministry of Rural Development and Family Farming, which had been shut down during President Jair Bolsonaro’s 2019-2022 administration.

Lula has also resumed talks with grassroots movements formed by peasants, rural workers and members of traditional communities, listening to their demands and creating government programs to assist them, the document said.

But those gestures were not enough, given that the budget for land reform and for family farming — through the National Program to Strengthen Family Farming (known as Pronaf) — remains low.

“While agribusiness continues to receive the largest share of public funding – as in the 2025/2026 Crop Plan, which allocated R$ 516.2 billion (roughly $100 billion) to the sector — family farming received R$ 89 billion (about $17 billion) through Pronaf in 2025,” the text read.

While Lula’s administration has been very cautious in advancing land expropriation and redistribution, it has opted for a specific approach to land reform, negotiating land purchases with owners rather than expropriating properties.

“There has thus been a shift from a policy of land expropriation to one of ‘negotiated acquisition.’ This strategy ends up serving more to ‘bail out bankrupt companies’ and solve agribusiness’s problems than to meet the demands of peasant communities,” the analysis went on.

According to Plácido Junior, a CPT coordinator in the state of Pernambuco and one of the authors of the document, the Brazilian government tends to see land reform as a kind of social program, whereas it should in fact be a broad structural reform of the Brazilian economy.

“The need to carry out land reform in Brazil is enshrined in the Constitution. But no president has been courageous enough to do it. It would transform the country,” Junior told Crux.

In the colonial era, vast portions of land along the Brazilian coast were distributed among Portuguese noblemen, who passed them down from father to son. Many of those lands ended up abandoned over the centuries.

At the same time, enormous territories — especially regions far from the coast and covered by dense rainforest, such as the Amazon — were considered vacant lands and were formally owned by the Portuguese Crown (and, after independence in 1822, by the Brazilian Empire).

With the proclamation of the Republic in 1889, part of those lands gradually became forest reserves, but many areas were invaded by ranchers who frequently forged deeds to claim ownership.

Poor farmers, Indigenous peoples and quilombolas — descendants of enslaved Africans who fled captivity and formed communities in remote areas — who had occupied those lands for generations have been systematically expelled – or killed – by land grabbers.

Today, that process continues especially in the Amazon, where many ranchers invade protected lands, deforest them and convert them to monocropping (especially soy and maize) or cattle ranching.

Last year, at least 26 people — including rural workers, Indigenous activists and quilombolas — were killed in land conflicts.

“That farming model is extremely harmful not only to people, but also to the environment,” Junior claimed.

The destruction of native vegetation and the cultivation of a single crop year after year lead to the intensive use of synthetic fertilizers and agrochemicals.

In livestock production, the dominant model tends to be extensive ranching, which leads to soil degradation, erosion, river sedimentation and contamination, as well as the use of fire to renew pastures.

“We’re in the middle of a climate crisis, and peasants and traditional communities know how to deal with it,” Junior said.

Indigenous peoples and quilombolas, unlike European peasantry, did not need to devastate forests in order to grow food, he said. In Latin America as a whole, traditional populations have not historically separated society from the environment. Production took place in dialogue with the biomes.

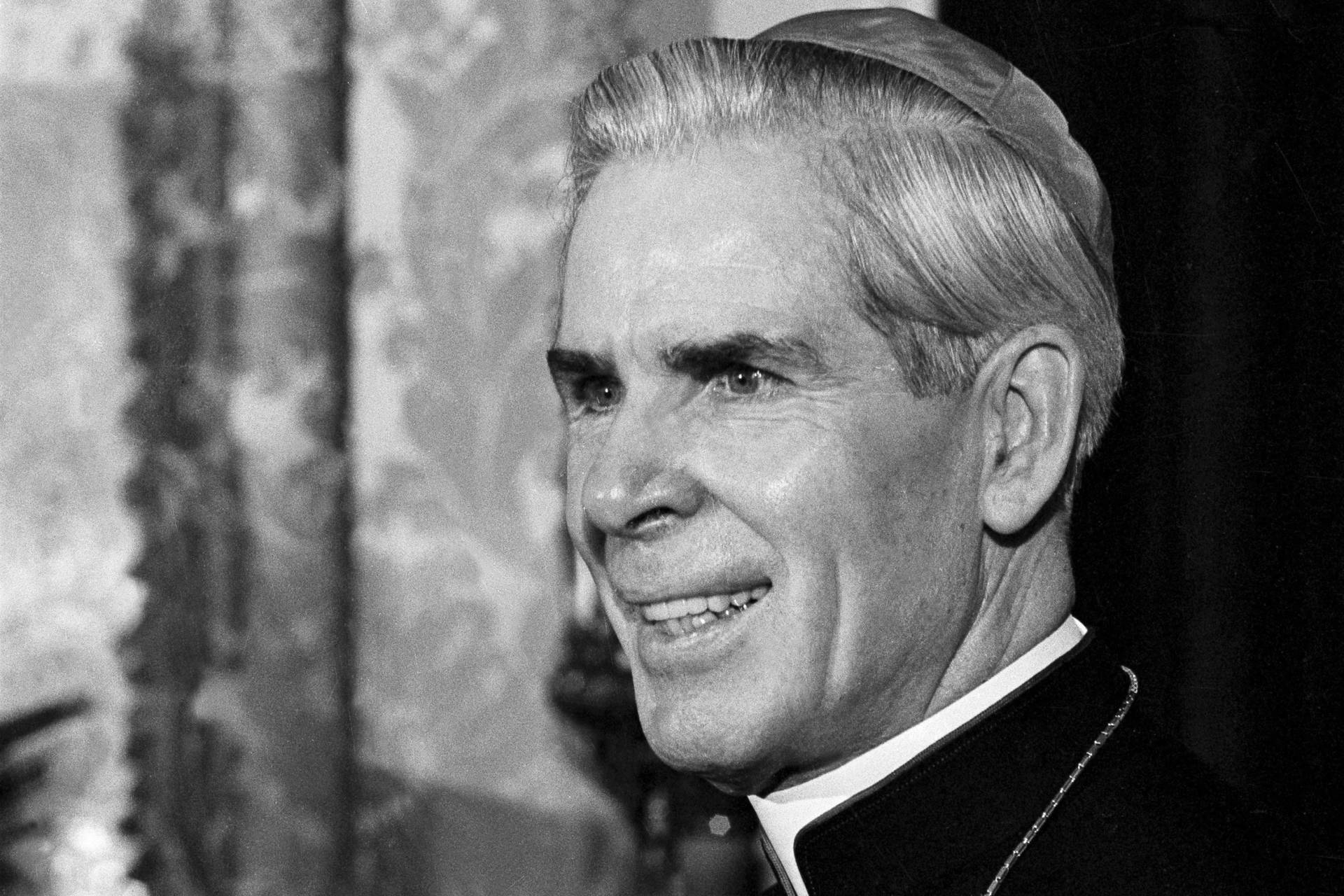

“Agroecological projects associated with land reform would drastically change Brazil’s current environmental crisis. Pope Francis understood that only under a different system would we be able to defend our common home,” he said.

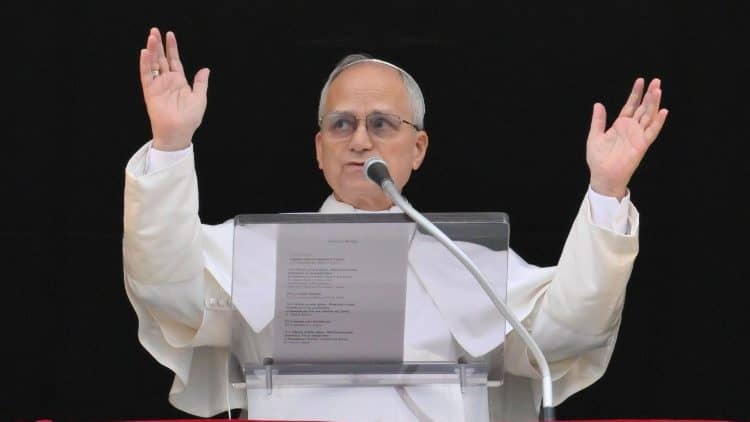

Bishop José Ionilton de Oliveira of the Prelature of Marajó, who heads the CPT, told Crux that Lula’s administration has undoubtedly made progress compared with Bolsonaro’s, which simply froze land reform. But the process has been too slow, he said.

“To promote land reform, the government needs support in Congress. But the current Congress is among the worst in history when it comes to decisions that favor the people,” he lamented. Lula has built a broad coalition that includes political blocs opposed to land reform, de Oliveira added.

Later this year, Brazilians will hold general elections, and land reform must be part of the political debate, the bishop said.

“We will work to ensure it is on the agenda of the next administration,” he said.